You know how some people just light up a room? Frida, a cane corso dog was not a person — though she didn’t seem to know it — but she brought light, joy, and a spirit of boisterous independence wherever she went.

Frida, the beloved canine companion of Ian and Barbara Bourland of Baltimore, was a participant in an osteosarcoma clinical trial at the Animal Cancer Care and Research Center in Roanoke, one of the three teaching hospitals of the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine.

Through her involvement in the clinical trial, Frida’s contributions are helping cancer researchers learn more about treating this deadly disease.

“To be able to treat her and to get more time and for that to have meaning beyond our love for her — that was the most worthwhile thing we could have done,” Barbara Bourland said. “I’m so grateful that we were able to participate.”

A “bait-and-switch” puppy

Frida came into the Bourlands’ lives in an unexpected way.

Their older cane corso, Hillary, loved the Bourlands but had little patience for other people or dogs. During a visit to the veterinarian, Hillary showed interest in a litter of cane corso puppies — this kind of curiosity was rare.

One of the puppies in the litter did not yet have a home, so the Bourlands began the process of bringing baby Frida into their lives. In a way, Hillary picked out a puppy for them.

During one meet-and-greet with Hillary, Frida laid quiet and asleep in Barbara Bourland’s arms, the picture of docility.

“What an exquisite bait-and-switch Frida pulled on us,” Barbara Bourland said. “She was the most active, brilliant, curious, demanding, chaotic dog I have ever known.”

The snuggly puppy grew up to be a headstrong dog who did exactly what she wanted, walking on the countertops and breaking out of any crate that dared try to hold her.

Frida maintained a robust social life. She loved going for walks because she drew attention wherever she went, and in the Bourlands’ neighborhood, she knew where all of her friends lived. She loved roughhousing with her pals at Good Doggie Daycare, but this 135-pound force of nature would become instantly docile around small children, letting them tug on her ears.

“Every day that Frida lived, she was truly alive,” said Barbara Bourland. “She made our lives bigger.”

As Frida aged, however, the Bourlands learned that Frida’s strength and joyous personality masked a lot of pain. When Frida showed signs of soreness in one of her front legs, the Bourlands and their veterinarian thought it was a torn muscle.

Testing revealed that Frida had osteosarcoma.

This painful, extremely aggressive bone cancer breaks down the structure of the bone and metastasizes to other organs.

Finding a care team

Frida’s osteosarcoma diagnosis was crushing, but the Bourlands knew they would do all they could to help Frida live her best life.

Just like with human cancer, animal cancer requires a team of experts to treat. After countless phone calls, emails, waitlists, and intake exams with specialists scattered across different practices, the Bourlands contacted the Animal Cancer Care and Research Center about enrolling Frida in an osteosarcoma clinical trial. They were immediately able to book an appointment and Frida found just the team she needed.

“It was very clear to me from the moment we got there that Virginia Tech was fulfilling its mission — every single person I spoke to was openly using their resources and expertise not only to help to treat our dog, but to inform us and to comfort us,” said Barbara Bourland

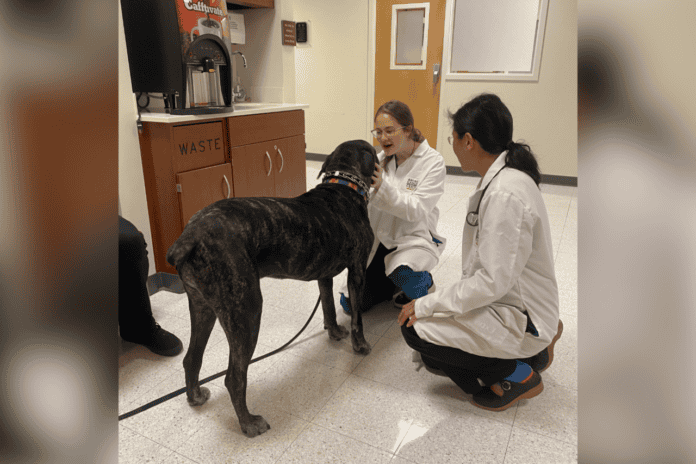

During Frida’s first visit to the Animal Cancer Care and Research Center, she and the Bourlands met surgical oncologist Joanne Tuohy, who led the osteosarcoma clinical trial.

“I think she’s the best doctor I’ve ever met, period,” said Ian Bourland. “Aside from being a brilliant researcher and surgeon, she’s a brilliant teacher.”

He joked that sometimes they felt like they were her graduate students because they learned so much from her.

In the coming months, Tuohy and the team would be instrumental not just in treating Frida’s cancer, but in providing support and guidance to the Bourlands as they worked through the emotions, grief, and tough decisions that come with a cancer diagnosis.

“There’s a sense of compassion [at the center], but also of curiosity and inquiry, so it was like we were collaborating rather than being just another customer. They were an exceptional veterinary team,” said Ian Bourland.

Study results may lead to earlier treatment

The Bourlands enrolled Frida in Tuohy’s study on histotripsy and urine analysis in dogs with osteosarcoma. Histotripsy is a technique that uses focused ultrasound beams to generate microbubbles in the targeted tissue. When those bubbles burst, they destroy tumor cells.

However, Frida’s tumor proved to be too large, and histotripsy wasn’t a good treatment for her. Instead, veterinarians amputated Frida’s affected leg to manage tumor growth and alleviate the pain, and Frida joined the study’s standard treatment group.

The team collected urine samples before and after amputation so that Tuohy and her collaborators can evaluate the utility of those samples for detecting the molecular signatures of osteosarcoma.

This technique, called Raman molecular analysis, was developed by John Robertson, professor emeritus of biomedical engineering at the College of Engineering‘s Department of Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics. Tuohy worked with Robertson and his partner Ryan Senger, associate professor in the Department of Biological Systems Engineering, to obtain the samples.

The potential impact of these urine samples is twofold. For one, this simple, noninvasive method can give oncologists a way to monitor the disease over time. Additionally, researchers like Tuohy hope that in the future, urine samples can be used to detect disease progression earlier.

Even after dogs with osteosarcoma receive amputations, the cancer still metastasizes, usually to the lungs. These dogs receive chest radiographs every few months to check in on the cancer’s growth, but that means that the lung tumors have to progress to a level in which they are detected on the X-rays.

With urinalysis, it may one day be possible to detect those changes earlier, leading to earlier treatment and possibly an improved outcome — not just for osteosarcoma, but for many different types of cancer. In addition to aiding in canine cancer treatment, clinical trials in dogs can offer insights into human medicine.

Quality of life

For the people-loving Frida, visiting the Animal Cancer Care and Research Center was an excellent way to make new friends. She soon had the building mapped out and knew exactly where to find her favorite people — and dog treats.

Her time at the center even seemed to transform Frida’s attitude toward veterinarians. When her primary care veterinarian removed her stitches after the amputation, he was surprised that she let him work on her without a fuss.

“She just let him do it. Because of her relationship with Dr. Tuohy, Frida’s relationship with our primary vet changed — she identified veterinary care with healing,” Barbara Bourland said.

“Something special is happening at the ACCRC [Animal Cancer Care and Research Center]. Even without it being about our dog, to meet a group of predominantly women scientists who have veterinary surgical specialties on one hand and Ph.D.s on the other, working together — so resourced, so supported — in pursuit of their goals is incredibly unique.”

In dogs with osteosarcoma, the cancer continues to metastasize in the lungs even after the primary tumor is removed. In human oncology, metastases are typically treated, but it’s far less common to treat metastases in veterinary medicine.

“I firmly believe that we can treat metastatic disease while maintaining a pet’s quality of life, and that’s exactly what Frida’s family did,” Tuohy said. “They tried this new combination drug treatment for Frida to try to slow down the metastatic progression in her lungs, and I think that’s another reason she is so special. Frida embodies what I hope to see in veterinary oncology.”

Attentive care at the Animal Cancer Care and Research Center helped Frida live a joyous life for longer. Frida passed away in November 2024.

Her story shows how one dog can have a big impact — her contributions will help Tuohy and other researchers as they develop more tools to treat osteosarcoma and other cancers.

“Even having suffered this loss,” Ian Bourland said, “it gives us meaning to have been part of this larger trajectory.”

By Sara Boudreau