Antonio Hash on deputy mental health, suicides in the jail, and his vision as Roanoke’s next sheriff

In advance of the general election on Tuesday, Nov. 2, The Roanoke Star is republishing interviews from the Roanoke Rambler with local candidates, including uncontested races, to give voters insights into who their elected officials will be.

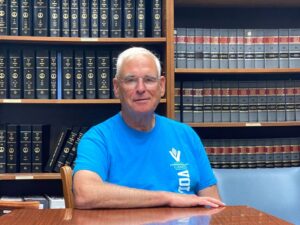

This week, we sit down with Antonio Hash, a 13-year veteran of the Roanoke City Sheriff’s Office. Hash, 42, is running as a Democrat to become the city’s next sheriff. The race is uncontested.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

What are the duties of the city sheriff’s office and of the sheriff?

For the sheriff’s office, we cover the court, we cover the jail, and we serve papers civilly from other agencies or jurisdictions in Virginia. They have to be served those papers, or papers to have people come to court for various reasons, and just to make people aware of their court dates. So that’s primarily our job. We do cover school resource officers for our schools. We do transportation.

You are currently a school resource officer?

Right now, I’m a school resource officer. The whole pandemic has pushed us into a position to where a lot of people, especially from a law enforcement side, are choosing other career paths. So it has caused setback when it comes down to law enforcement because we don’t have the people employed to be able to continue to hold up our end of the bargain when it comes down to the schools. And so I am out here on the [campaign] trail like, ‘Hey, we are hiring.’ You know, the sheriff’s office needs people, the police department needs people. I enjoy working with our kids from our community. It just gives you a sense of gratitude that you pour back into somebody else’s kid, and seeing something good in them so they can move on with their life and be able to become a productive citizen like we are.

And what school do you cover?

Currently I’m at Hurt Park Elementary School, I’m at Roanoke Academy [for Math and Science] elementary school, I am at Fairview [Elementary School]. And I am at [Lucy] Addison Middle School. So, we short. When it comes down to our schools, we are out here, we are trying to engage our students with the help that we do have. So, we trying to make the best out of it.

Why do you want to be sheriff?

For years, I’ve sat back and I’ve watched the growth of our department. And we have had some great leaders. But there’s things that need to be changed. And a lot of times, people won’t allow change, because they’re in a position to where they’re scared of what people may think. And even though I care about people’s opinion, but when change needs to happen, the only way you’re going to be able to get there is to make the change, or to implement it and allow change to happen. If it doesn’t work, don’t be afraid to say, It didn’t work, and then go back to fix it, or go back to something else that was working. But if you never implement the change, you’ll never know what’s going to work. So over the years I’ve seen things that needed to be changed, just haven’t been changed. We need some more diversity in our department. Again, people need opportunity and it shouldn’t rely on just the African-American community or the Caucasians, but any ethnicity that wants that opportunity if they meet the guidelines or credentials to be a law enforcement officer. Roanoke is a diverse city. And when you look at law enforcement, the law enforcement family should look like the city who we serve. I don’t care what’s your background, your sexuality, it should look like the city who we represent. And so I’m trying to grow our department to look outside of the box, look outside of the norm, you know. We’ve been brought down the same way for 13 years, let’s change some things. And don’t be afraid to change it, but it’s gonna take a person like me coming into office saying ‘It’s broken. Fix it,’ you know? And I’m not saying everything about our department is bad, because we have great things about our department and great things about our city. But when change needs to happen, you need people like me that’s going to implement change.

Specifically, what things would you say are broken and what needs to be changed?

So, I don’t want to go into too much detail because I’m still an employee, and I don’t want to step on the toes of people who are in charge of me. But what I can say, when it comes down to our mental health, I’m going to create change around mental health. I’m going to create change around diversity. I’m going to create change about recidivism and what we offer as far as our reentry programs, because again, people do make mistakes. But people deserve opportunity to change. They committed a crime, but they’re still going to be productive citizens one day, they’re going to return back to our community. And if we don’t give them some stability, they become reoffenders again and this time it may not be against these families over here, but it may be against your family or my family. So we have to offer services to these individuals. We have so many agencies and nonprofits around the city who get paid to put on programs for the community, but people are not taking advantage of these opportunities, because they’re sitting in jail. We have to create opportunity, jobs, housing, services. The city offers it, these agencies offer it, so why not give it back to these individuals. Because if we don’t give them help, they’re going to reoffend again. The city offers a drug program for those who are on drugs called the Alpha program, or drug court. Those individuals who want it take full advantage of it. But those individuals who cannot get themselves together, the system is set up to help them, but maybe their rehabilitation part is not going to work for them they need time to sit down and get their lives together by taking them out of the environment they were in, they put them in a situation to where they out here, using reoffending, causing harm or danger to our community.

Your campaign website talks about mental health both for those incarcerated as well as for deputies. What do you plan to do on the deputy side to help people with mental health?

So, from a deputy standpoint, we come to work every day. When you walk in, the door shuts behind you, too, so mentally, it puts you in a position to where it’s almost like you’re locked up, too. The great thing about it is at the end of your 12-hour shift, you get to go home. But when you come inside the facility, there’s no windows, you don’t see the sun, you don’t know if it’s raining, you don’t know if it’s snowing. We mentally and we physically experience so much being inside that type of arena to sometimes when crisis hits, it hits those loved ones or those loved ones that are in our facility, but when the deputies have to experience the crisis, when they have to experience the emergency, it plays on their psyche as well. So what I’m telling our deputies, when we experience crisis, you have to go get help as well. That way we can make sure that you don’t break down the integrity of the job, because if integrity is broken it leads to other things. The City of Roanoke offers assistance now to employees. But it’s going to be our job to mandate and say, ‘You have to go before you can return back the next day or this week. You’ve got to show us that you’ve been and you received some type of help.’ Because it’s needed. It was never encouraged.

You were born and raised in Roanoke?

I’ve lived in Roanoke all my life. I moved away to D.C. and Richmond for a little bit. And then I moved back to Roanoke, where I worked. I was a barber at one time, cutting hair. I loved it, it was an amazing profession. Then I went to banking, for Freedom First [Credit Union]. I went to the DMV, worked for them as a window clerk, amazing job. But then I had the opportunity to join the sheriff’s office because I wanted something on another level to be able to serve our community. And when I put that uniform on for the first time, and put my badge on, I felt like I had something to give, I have something to offer.

What inspired you to go into law enforcement?

I forgot to say that I was working at a phone company, and some of my good friends, they was like, ‘We getting to join the sheriff’s office,’ and I was like, ‘For what?’ and they were just like, ‘You know, we just want something different, and it’s awesome.’ Okay, so I was riding down the street one day, I looked over to my right, and this deputy sheriff pulled up next to me. He looked over and he just smiled like he was enjoying his job, and I was like, Man, I would like to work there, you know, just because when you find folks enjoying a job, smiling, it’s just like, ‘Okay, what’s so blessed about being in the sheriff’s office?’ I put in an application and I had an interview, they gave me a tour the facility. I was like, ‘This is wild, but I think I want to be here.’

I read that your father passed when you were in fifth grade—

I never knew my father. My grandmother helped raised me. My mom was a wonderful lady, single mother. She gave everything to make sure her kids never lacked anything. She was a hairstylist. My mom would try to make ends meet, do the best she can.

I met my father once. It’s crazy because I met him at our child support case downtown. It was Halloween day, and they were having a Halloween costume party at church — they called it the Hallelujah Night. And my dad said, ‘Hey, I’m gonna go down the street and get him a costume.’ So we sat outside the municipal building, and I think it was the Heironimus building downtown. He said, ‘I’ll walk down the street and get you a costume.’ And we sat there for an hour and a half. He never returned.

So that was my last memory of my father until the day he died. We went to see him in the casket and he was laying there. It was emotionally hard to deal with it, because here it is somebody who helped to see the birth of you, but never was a part of your life. And so at first I couldn’t cry. I couldn’t do anything. So it put a bitter place in my heart. But then I got older, I was like, Lord, if it was meant for him to be there, he’d still be there.

In recent years there’s been significant concern about the jail’s high number of suicides relative to the population incarcerated. Experts note that jails are ostensibly fully controlled environments with cameras, tear-resistant sheets, etc., that there shouldn’t be any way for a person to kill themselves in a cell. What specific policies would you implement to prevent suicides?

Our job in our jail is to identify anybody that is in crisis. The problem that we have is people have been in our system for so long, they have learned the conversation, or the way we communicate with them, when crisis is in front of us. And so they know what to do, what to say and how to skate around it. ‘Sir, are you homicidal or suicidal? Do you feel like hurting yourself or anybody else? Have you already tried to commit suicide?’ And the first thing they tell us is, ‘No.’ But when they get back in their cell and they locked up, they think about the things they’ve been through in life, the charges they’re charged with, [they start thinking] ‘I’m done, it’s over.’ If we don’t see them in the moment, we don’t catch them. So then we try to teach other inmates, if you see something, say something.

We are a non-direct supervisional facility, which means we are not in there with them. So twice an hour we are doing our rounds; you know when we are coming around, so we can stagger our rounds. But if we just left your pod, typically we aren’t back there in 30 minutes. Thirty minutes is a long time to make something happen. If they slip through, because they know the process, then our job is to try to catch them, but we don’t catch them all. And I hate to say that, because they’re in a facility that they can trust us, that their loved ones there are taken care of.

We do have the sheets that after so much weight or pressure they’re supposed to tear, so it’s not supposed to allow them to hang themselves. Our razors now have a device on them so where if you break it, it is no longer usable. We are taking training, we are looking at other institutions and seeing some of their training that they have across the board, that could assist in a correctional facility, dealing with the suicide rate. A lot of institutions are dealing with the same thing. But we try to catch everything that we possibly can, because it is our goal for you to return home to your family.

But what about any specific policies that you think need to be changed, in terms of hard infrastructure, like new staff, new cameras, anything?

So right now every pod has cameras inside the pods. The only places they don’t have cameras is inside the cells because of people’s privacy. Every day room has cameras, every suicide cell has a camera. We have a mental health pod. We have a whole section now that is set up so these individuals can get help as soon as possible. So we have implemented that over the last three years. It is my goal to continue to make sure that we are staffed in those areas because building those suicidal pods or mental health pod, that helped our suicide rate go down, just because we’re now being able to identify those individuals sooner than later. And they’re able to get them some help, get them evaluated, get them on medication.

Some localities are trying to do things where people with substance use disorders, like alcohol, instead of going to jail, they would go to some other sort of detox facility—

Absolutely. I was watching the news the other day and I saw jurisdiction nearby. They have the funding that allowed them to instead of bringing those individuals to jail, they take them to this facility to where they can get help ASAP because they realize jail is not meant for this person. They didn’t commit this crime because they were criminals; they committed this crime because of mental health. I would love to partner with anybody who may think that we can bring something new to our city, to be able to service these individuals or to push them forward. Again, if the opportunity is there, I’m taking it.

In recent years, there’s been increased awareness of and attention to systemic racism, particularly as it manifests in the criminal justice system. What role do you think the sheriff’s office has in addressing those inequities?

We create opportunity across the board for those individuals who we feel like need an opportunity. And it’s not the same across the board. I’m trying to work with the Commonwealth to say, ‘Hey, let’s implement programs to where we’re not just sending, you know, Black people to jail because we feel like that’s the best place for them, or Caucasians to jail. Anybody who has committed an offense for the first time, let’s create opportunity for them to where we can get services from them because they committed a crime. So now they’ve given you a resources back to the community, community service. One of our things we wanted to do was a workforce program. This will allow us to utilize the services on the weekends. So now we just put them in jail, Friday, Saturday, Sunday, or Saturday Sunday now. But instead of putting them in jail, we put them out to work.

You’ve got to tell the Commonwealth’s Attorney, we have to make sure that people are being convicted across the board the same, because in one culture they may not be able to afford an attorney, but in one culture they can. But this one don’t get the same services as this one over here. It has to meet across the board.

The Roanoke Times is good at showing up in court, and hearing cases out, and then documenting and putting it on the front page: ’40 years in jail.’ But then the next thing happens: two years in jail for the same crime, but the weight doesn’t carry the same for different cultures. And that’s what has caused a lot of division in the criminal justice [system], because people see it, you know, so they feel like they’re not treated fairly. They feel like they’re being targeted for certain crimes because, you know, my windows are tinted, that doesn’t make me a bad person, but another person can get away with the same thing. We have to do better as a country, as a community. Roanoke has, for the most part, we have held it together on the home front. We ought to be commended, because Roanoke is not like some of these other cities. Do we have some opportunities to grow and make things better? Yes, but we don’t look like some other cities.

What’s your position on specific reform ideas such as ending cash bail or ending mandatory minimum sentences?

I don’t want to end cash bail. I feel that if a person has the ability to bond out, let them bond out. Some of the cash bonds that they make people pay are getting put towards their or child support or certain things in order for you to get out.

And what about mandatory minimums?

I’m not against the mandatory minimums. People know when they out here committing crimes what they are getting themselves into. And if you don’t, you need to look it up. I’m not against it because it holds us accountable for the things out here that’s plaguing our community, gun violence, selling illegal drugs. People are dying from homicide, you know, all kinds of stuff. So there has to be repercussions for the things that you do.

Outside of work, what do you like to do for fun?

I love doing community service. Every year, called the UBU Honors, we honor people, organizations, legends in our communities who give back. I’m a singer. At one time I was a youth pastor. I love ministry, I love church, I love my community and I love family. I play volleyball.

What else do you think is important for voters to know either about yourself, the office or the election this November?

At the end of the day, it is my goal to lead the people of Roanoke City as a true leader, lead them with dignity, lead them with respect. The community is looking for an outlet, they’re looking for change. But somebody has to be the voice of reason, somebody has to be the change that you want to see. I will never ask my deputies to do something that I’m not willing to do.

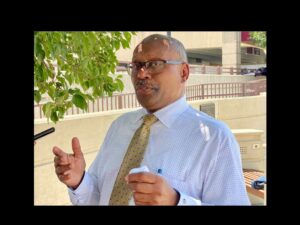

Donald Caldwell on the failures of criminal justice reform, systemic racism, and his final run for Commonwealth’s Attorney

This week, we sit down with Commonwealth’s Attorney Donald Caldwell, who is running as an independent against Democratic nominee Melvin Hill. The Roanoke Times has written:

“For longer than the Roanoke City Courthouse has stood at Church Avenue and Third Street, longer than the tenure of its most senior judge, longer than the time spent in prison by many a criminal who passed through the building, one thing has remained constant: Donald Caldwell has run the prosecution.”

That story was published in 1997. Caldwell, 70, became Commonwealth’s Attorney in 1979 and has faced a challenger only once, in 2017, when Hill ran against him.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Why are you seeking another term?

I’m seeking another term because I feel the integrity of this office, and the reputation of the city, is at stake. For whatever reason, Mr. [Melvin] Hill has offered himself as a candidate, but he has a background of financial troubles, of breaking the law, of not paying his federal taxes over many, many years, of using the bankruptcy system to eliminate his debts to people that he’s received goods and services from. He’s done that twice in his career, both Chapter 7 [bankruptcies], just eliminating all of these debts. Integrity of the office is one reason I’m running. The second one is the reputation of the City of Roanoke. It’s my belief that a city, just like an individual, has a reputation. And if a city gets a reputation for electing leaders who can’t manage their money, and are not holding themselves to high standards, then that will be the reputation that Roanoke gets. And of course Roanoke, like every other city, every locality, competes for business, and I don’t think that’s a good message to send. So part of this is, you know, Roanoke has been good to me, and I’m trying to return the favor.

Would you have run for reelection if Melvin Hill were not the Democratic nominee?

I would not have. The short answer is if a qualified candidate — and of course people could say, Well, what’s your definition qualified? — but if a candidate had been put up that appeared to be qualified on their face and had a good reputation within the community, I would not run again. And actually, I wouldn’t have run four years ago had not Mr. Hill jumped in. I mean, Mr Hill’s strategy is pretty plain and simple. He feels like being the Democratic nominee in a city that votes primarily Democratic, that he can ride the coattails of others to office.

Do you think it’ll benefit you that there’s no party affiliation on the ballot? It’ll just show up as Don Caldwell, Melvin Hill.

It’s hard for me to predict, because I’m not that astute on politics. Obviously, my main strength is that I have name recognition. I’ve been here a long time. And I don’t believe I’ve ever done anything to embarrass myself personally or the office personally, so I think I have a good track record. And I realized that no, not everybody agrees with everything I do, but that’s just the nature of being in a job where you have to make decisions.

Where we are in Roanoke right now is there’s very much frustration with the level of violent crime, very much, and I see that. I think it is a problem for the police, it is a problem for this office. But there is apparently — since this is a country-wide phenomenon that we’re dealing with right now — nobody seems to have come up with a real good answer at this point in time. So I don’t think the police should be blamed. I don’t think this office should be blamed. We do the best with what we’re given. Currently, I pretty much think that we’re reaching a crossroads in this country. After eight years under the umbrella of criminal justice reform, it does not seem to have produced results. It seems like we have a situation where many, many people have no respect for the law, they don’t have respect for authority. The focusing on the offender, as opposed to the offended, doesn’t seem to be panning out. But it is going to take, I think, some of our elected leaders — and I’m not talking about the Commonwealth’s Attorney — I’m talking about the police department, I’m talking about our council people, our delegates, our senators, our congressmen, our representatives across this country to stand up and say, ‘We’ve had enough of it. And we’re going to have to take a harder stance.’ And, you know, we use this phrase, ‘mass incarceration.’ I’m not sure it ever was true. I don’t accept it as being true, but it was presented and apparently accepted by a lot of people as true. But when you’ve got people who are incorrigible and will not follow the law, I think this society has to decide whether it’s worth investing in the resources to remove them from society until they can conform their conduct to the law. And of course, necessarily that means that you’re going to lock up some young people, because those are the crime-committing years, 18 to 28. You know, a lot of young men, if somehow you can carve out and just say, We’re going to shorten your life by 10 years, but we’re going to get you from the maturity of 18 years old, immediately to the maturity of 28, a lot of this crime in the country would not happen. Testosterone, for lack of a better phrase, the stupidity of youth, if you didn’t have to deal with that, we’d have a lot less crime.

What are some of the reforms that have taken place here locally that you think have not panned out or not worked?

When you say locally, I’d say you’ve got to go to the state level to address most of the problems. I would say that the elimination of petit larceny felony offense for people who habitually steal is one that I think is particularly short-sighted. There are people out there that like to steal; they don’t steal because they’re hungry. They steal, primarily, to convert the money into drugs. But I think the elimination of that tool in the arsenal, so to speak — I’m not talking about people have to go to jail for the life or anything like that — but you have some substantial punishment. I think the elimination of jury sentencing is a big thing. Of course, I have to laugh with the elimination of jury sentencing, because still the defendant can ask for jury sentencing if he wants it, but yet the Commonwealth can’t. So, to me, it’s an odd juxtaposition of rights. One side can, and the other side can’t. Virginia had a very simple process, and on a lot of the major crimes, the ability of the jury to weigh in with the community’s thought on it resolved a lot of cases. And now we made the system that much more cumbersome because you’re seeing, as was predicted, an increase in the request for the number of jury trials. And that’s because of the elimination of jury sentencing. Most of those changes have taken place in the last two years once the [Virginia] House [of Delegates] and the [state] Senate went under Democratic control.

Another thing that I want to mention, because I feel like people are very much frustrated with the — I’m not going to call them homeless, this is what I’m wrestling with. A lot of people say, We have problems with the homeless. And that implies that there’s no will on their part, and they’re homeless because of bad circumstances, But we have a lot of people on the street who some circles would call homeless, but they’re homeless by choice. That’s how they want to live. They don’t want to go to the [Roanoke] Rescue Mission because, guess what, the Rescue Mission has rules, and they don’t want to follow the rules. So they’d rather be out in the street begging, they’d rather be out on the street using alcohol, things like that. So there’s a lot of frustration with that. And one of the things that we’ve lost in the last four years is the interdiction statue, the habitual drunkard statute. That was ruled to be unlawful by the [federal] Fourth Circuit [Court of Appeals]. And what disappointed me was that there was a very, very strong dissent in that, and the dissenting judges encouraged an appeal by the Commonwealth of Virginia to have that heard. And our Attorney General did not appeal. And I felt like he didn’t appeal because he felt like he was on the side of the person with the alcohol problem. So there was an opportunity to at least try to do something that could help the average citizen or businessperson who doesn’t want somebody laying drunk in the doorway of their store. But that opportunity came and went, and the Attorney General did nothing. So, those will be some examples of things that just are very, very frustrating right now. I could throw in as one last thing: the legalization of marijuana without a legal source. I mean, I could care less about the policy decision, which is the General Assembly, that we’re not going to treat marijuana as a crime. It looked to me like the first thing they should have been doing is saying this is how we’re going to provide the stuff legally. Because right now, it’s boom time for the drug dealer. And of course, as we all know, a lot of violence surrounds that secondary economy.

There’s been talk about some reforms that haven’t taken place, such as ending cash bail or ending mandatory minimum sentences. What’s your position on those ideas?

They’re coming. In some instances, they’ve already taken effect. The no-cash bail, that’s an illusion. That is a publicity stunt packaging among progressive prosecutors. It sounds good, but I’ve looked at how they do it in Northern Virginia. Earlier this summer we had a presentation on no-cash bail. And it really should be no-cash bail unless one’s needed, which is what we’ve always done. Most people do not put up cash anyway. They have a bondsman come up so it’s not really cash in that sense. Now, they do have to pay a bondsman some cash, because bondsmen don’t take credit, just like drug dealers. I’m not a fan of the progressive, so-called cash bail move.

What about the argument that people with means are treated differently. Why wouldn’t it be that—

Life is not fair.

Why wouldn’t it be that somebody is just held in jail, versus being able to post a bond?

The point I’m trying to make is people who come into the court system the first time, unless it’s a violent offense, are released on their recognizance. It’s only when you start developing a track record of continuing criminal activity or failure to appear for court or, then, the third category is you commit a violent crime, that’s the people who come in and stay in jail or have to post a bond.

The argument about it going back to somebody who’s got money, that’s a fair statement. But, you know, that is true if you’ve got more money, you’ve got more ability to have better resources. You’re either gonna have to eliminate the private defense attorney, and we’re all gonna be state defense attorneys, or you’re going to have to say, Well, the state is going to pay its attorneys just like the private attorneys are paid, and that’s not going to fly either. But I go back to sort of my fundamental rule, which is, Number One, Life’s not fair. Why do some people get cancer and other people don’t? I mean, it’s just because life is not necessarily, universally fair. You know, the current saying about, We want justice. Well, you know, I hear what you’re saying, but by the same token, I’ve got a saying that’s evolved over the years: ‘Justice, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.’ And that’s why when a judge opposes a sentence in court, you don’t usually have both sides standing up and clapping saying, ‘Man, that is justice. That’s right on.’ One side or the other is probably not as pleased with the outcome. So if you asked one side, ‘Was justice done?’ ‘Hell no, justice wasn’t done,’ the other side would say, ‘Oh yeah, justice was done.’ True neutral justice, just like handing King Solomon the sword and saying ‘We both want this baby.’ Wack! So, I don’t know.

What about mandatory minimums?

I’m against the elimination of that. I hate to sound harsh, but there needs to be a hard line taken on some sentences. I’m a fan of mandatory sentencing for certain violent offenses.

I also hear a lot of concerns from people in the community about the uptick in shootings and gun violence recently. Is there anything your office is doing differently to address the crime?

I mean, my people don’t shoot anybody, so I’ve held a line on that. So I don’t feel like we’re doing anything to contribute to the shooting. In 1994, there were only three homicides in the City of Roanoke. I was on NPR talking about the downtick. And they asked me at the end of the thing if I had anything else to say, and I said, ‘I take neither the credit nor the blame.’ These are forces that are outside my control. We’re responsible for the prosecution of cases when they come into court. They have to go through the police to get here, the police have to get cooperation from the citizens. That is particularly frustrating right now.

The community is frustrated. But once again, I think it’s not so much the police or this office, but leadership of this state, from the governor on down to the lowest ranking member of the City Council, or your Board of Supervisors, has got to say, ‘Enough, we want it stopped,’ and they’re the ones I really do think that have got to stand up and say, ‘I don’t care how old the defendant is, I don’t care what the race of the defendant is, I don’t care how many bad things happened to him as a youth, but if they kill somebody or hurt somebody, we want him to go to jail.’

Are there any specific new policies or actions that your office is looking to put in place if you’re reelected?

We need to develop an attorney position that is dedicated to elder crime. And that’s a growing concern. It’s been showcased some during COVID about the care in nursing homes and things like that — a particularly complex situation where the regulations and the law are not really conducive to holding anybody truly accountable to the things that happen.

In recent years, there’s been an increase in awareness of, and attention to, systemic racism and structural racism, particularly as it manifests in the criminal justice system. How would you say your views have evolved when it comes to the existence of racial disparity in the system at large?

Once again, I find myself in the position of not necessarily agreeing with a lot of the information that is put out. I know that this office, and I don’t think the police department, and I don’t think that the courts, are treating defendants that classify themselves I guess as a minority, because I guess if you’re talking race, you got white, you got Black, you got red, you get yellow, I mean, whatever the umbrella of racism that you’re talking about. But once again, when we go back and look at the crimes, violent crimes here in the city, look at the homicides for this year, the vast majority of the offenders have been Black. The vast majority of the victims have been Black. So, if you took a snapshot in time and we were able to successfully prosecute them all, you can get up and say, ‘Well, gee, everybody’s going to jail is Black.’ I don’t know how you get around that. I think we’d be a better society if we would quit focusing so much on statistics and go to just focusing on the person, whatever race, whatever creed. Addressing the person individually without so much concern about what race they are or are not. I personally don’t see that as a big issue in Roanoke City. I’m sure others will disagree, but that’s my position.

It’s trickier to get statistics from the court system. But state police data in Roanoke show that recently Black drivers are twice as likely to be searched when stopped than are white drivers. And some recent data specific to Roanoke City Jail show there’s a greater proportion of Black people incarcerated than they make up in the general population. I’m curious if your office tracks—

No, we do not. We do not have a statistician or anything like that. But once again, to me, you shouldn’t worry so much about the race of the person involved. It’s, is it a legitimate connection to a criminal situation? Now, if it’s trumped up or, you know, it’s an illusory thing, that would be my concern there. But, I mean, it bothers me when we start focusing on statistics and sort of lose the overall vision. What’s the racial makeup of this country if we’re just talking about Black people in this country?

I believe it’s 13 percent.

You’re exactly right. What is the racial makeup of the NBA [National Basketball Association]?

That I’m not sure.

It’s like 67 percent Black and the NFL [National Football League] is 70-something. You could look it up. All right, are those both racist institutions? Statistically, yes, wouldn’t you say?

Well, I think it’s hard to—

It’s a brain tease, is what I’m saying. I brought that up at a meeting on the juvenile justice system about a year ago, because the presenter got in there and he says, ‘Everybody’s talking about race,’ and then he went off on his spiel that there were too many Black kids in the juvenile justice system. And so I raised that question, I said, ‘Okay, I’m not afraid to talk race.’ I said, ‘The Black population of the United States is about 12 percent but the NBA is like 67% Black. Why is that?’ He said, ‘I don’t know,’ and I said, ‘Well I don’t know either.’ I mean, I really don’t. But I would say it has something to do with their skill and ability, and I said, ‘I would conclude that most of those Black players are there because they deserve to be. And I would also say that most of the kids in the juvenile justice system are there because they earned the right to be there, they’re just like the NBA players.’ And so, I don’t know. It’s a complicated thing.

What about when it comes to criminal justice matters; you mentioned the majority of offenders and victims in shootings are Black in the city. Why do you think those disparities exist?

That’s a good question, and that could be a whole separate subject. If you have a 20-year-old that shoots somebody without provocation, and just shoots for a few dollars out of a cash till, when did that kid start going, when did that start? Was it a genetic thing that started right, you know, when the sperm and the egg united? Was the die cast then, or is it something that just goes on down the road? But predictively, I would argue that, it’s going to show that this young man now didn’t really have much parental upbringing. Probably a single mom, if that, maybe grandparents. I would say that their opportunities to get involved in the educational system early — like pre-K or kindergarten or preschool something like that — probably didn’t have that. Probably did not have somebody at home that was making him do his homework. Got siphoned off as a 10- 11- 12-year-old by the allure of the gangster life. By the time we sit him down here, the traditional institutions that sort of shape a person — your parents being one institution, the school system being another institution, and then religion, church, being an institution — those three big societal institutions that have been around thousands of years. But now we see the breakdown of the parental unit. Our schools are not succeeding with this group. And the churches are almost totally out of the picture. And so, you know, how you interrupt that and how you change that, how you can change it? But that’s where I think a lot of our problem is coming is showing itself now. But you the beginnings of that problem go back 20 years, 15 years, 14 years. If there was one thing I learned in that aborted race against [state Senator] John Edwards, we would be better off as a society investing in pre-K and getting all of our kids into some sort of structured teaching, exposure to teaching. We would really be better off to double down on our efforts to encourage young people not to have children until they’re a little older, because so many of them just don’t have the resources or the training to really care for children, to raise them. So, it’s a huge problem. If I had a good answer for it, I’d give it to you. I recognize the problem. I don’t have a solution.

You mentioned the aborted 2015 race. Do you regret that at all?

No. I just felt an itch that had to be scratched. I just wanted to try to make a difference. I didn’t realize I’d get clobbered as badly as I did, but then, on the other hand, you know, that’s just life. [In 2015, Caldwell ran as an independent against Edwards and lost with 6.4 percent of the vote.]

Does that itch, more for involvement in legislative politics as opposed to prosecution, does that still exist?

No. I’ll be 71 in November, so I can tell you right now this will be my last run. And I don’t have any aspirations for anything else.

Outside of work, what do you like to do for fun?

I’m big into cowboy-action shooting. That is probably my biggest hobby right now. It’s just a competitive sport using Old-West type guns — revolvers, lever actions. And your shoot steel targets against the clock. But it’s sort of like the way our school system has become. We’ve got so many categories and everybody can be a winner, so you always feel good after a match, because if you put yourself in the right category, you can you can win the little badge.

What else do you think is important for voters to know either about yourself, the office or the election this November?

My summary thought is that I’ve always tried to do the best job I can. I realize it’s not perfect, but I’ve always tried to do it honestly and with integrity. And I have not been an embarrassment to this city, and I can promise that that will continue for at least another four years.

*******

Melvin Hill on gang violence, drugs, and why he’s running for Commonwealth’s Attorney

Melvin Hill, the Democratic nominee for Commonwealth’s Attorney, and his campaign did not respond to numerous requests over multiple weeks by The Rambler for an interview. On Monday, Hill spoke to The Roanoke Times about his medical issues and financial struggles — which include a 2020 bankruptcy declaration after Hill faced hundreds of thousands of dollars in federal tax debt.

Today, we’re publishing an excerpt from Hill’s announcement speech about why he’s running for Commonwealth’s Attorney — a position he sought in 2017 — against incumbent independent Donald Caldwell. The kick-off in August, which occurred before revelations of his more recent financial troubles, ended with questions from the media, which came from The Roanoke Times and WFIR radio.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

I’ve been asked during this campaign. Why should I vote for you? Why are you running? And the thing I tell people is, if you could compartmentalize it or reduce it down to a phrase, it is experience and new ideas. First of all the experience, that’s life experience, and that’s experience as a lawyer. First and foremost, I was born in 1956 in Lynchburg, Virginia. My mother and father were divorced, so I was raised by my mother, as a single parent in the first housing project in Lynchburg, Virginia. There were three of us. I have an older brother and a younger sister. I was the well adjusted middle child. There was a lot of discipline, a lot of love in that household. For example, I still remember that my mom would make my sister sit at the breakfast table, even though she did not eat breakfast, because she had that order. Got up, got ready to go to school, got packed, when you got back from school, you did your homework. So that’s kind of the background that I grew up in. And then, in that background I learned accountability. And that’s at bottom what the criminal justice system is about. It is not so much about putting people in jail. That’s what people normally think. It is really about holding people accountable.

Now, I graduated from E. C. Glass High School in 1974, Saint Paul’s College in Lawrenceville, Virginia in 1978 and W&L [Washington and Lee] law school in 1983. I’ve been a lawyer since 1984. As a lawyer, I’ve done virtually almost everything a lawyer can do. I’ve been involved in at least 200 jury trials as a prosecutor and a defender. I’ve represented clients who have appealed to the Supreme Court, and to the Court of Appeals of Virginia, I’ve represented clients in civil cases, represented clients in divorce, custody cases, all kinds of family law cases. I served on the [city] planning commission for two terms, a total of eight years, and I’ve also served as a substitute judge. The only reason I resigned from that position as a substitute judge was to run for the office of Commonwealth’s Attorney. As most of you may know, you cannot be involved in politics and be a full-time judge.

I bring that experience to bear on the office of Commonwealth’s Attorney. And because of that experience and life experience and that experience as a lawyer, the platform that I am running on is several things, but primarily, it’s community-based prostitution. Now, there’s been almost an epidemic of gun violence across the nation and specifically in the City of Roanoke. So the question then becomes what do you do about it? There are two avenues you have to go down in my opinion. You have to be involved in what’s called intervention. You have to be involved in incarcerating those dangerous individuals participating in gun violence, shooting people, shooting cars, shooting houses and so forth. There is no excuse for that kind of behavior, and it will not be tolerated when I’m Commonwealth’s Attorney of the City of Roanoke.

But the other part of that — what is missing now — is, specifically, prevention. You got to be involved in the community as the Commonwealth’s Attorney. You have to go to the churches, you got to go where the young people are, you have to go to the schools. You have to go to nonprofit organizations.

Another aspect of my tenure as Commonwealth’s Attorney is specific to gangs. In the last few years, a lot of gun violence has been perpetrated by gangs. So what do you do? Gangs recruit people from the elementary, middle school and high schools, people without a criminal record. So with the new sheriff, Antonio Hash, hopefully I will be able to partner with their program and prosecutors will be involved in talking to young people, and those levels — elementary, middle school, high school level — to prevent people from getting involved in gang activity in the first place. I will dedicate two assistant Commonwealth’s Attorneys to a gang intervention unit.

What I hope to be is not the kind of prosecutor that comes to a woman and says, ‘Ma’am, we were able to successfully prosecute your son’s killer and he’s got 30-40 years in the penitentiary.’ I want to be the prosecutor who comes to the citizens of Roanoke at the end of four years and says, ‘I have been able to reduce gun violence by 10, 20, 30 percent.’ If I am successful in that, I have saved lives. The other aspect of my tenure as Commonwealth’s Attorney will be drug treatment, as opposed to incarceration. There are studies that indicate that if just 10 percent of drug users were given drug treatment, as opposed to incarceration, we’d literally save $4.5 billion. So my focus will be on drug treatment, rather than incarceration. Specifically, I will ask for an expansion of the drug court program. The Commonwealth’s Attorney’s Office gets a veto over who gets into the drug court program. We will expand that and make sure that everybody who has a serious drug addiction can get into that program. There’s the Alpha in-jail drug treatment program [at the Roanoke City Jail]. We’ll be liberal in allowing people to get into that program. All of those things we’ll be doing to get more drug treatment to these people who seriously need it.

Also, I’ll be partnering with the legislators, Sen. [John] Edwards and Del. [Sam] Rasoul, to expand the funding for drug treatment.

If there’s a drug treatment center on every corner — I’m just exaggerating, obviously — but if there’s a drug treatment center and everybody who wants to avail themselves of drug treatment actually takes part in that, that will save lives, save money as well. The cost of incarceration is greater than the cost of drug treatment. Those are simply two of the things I’ll be doing: the community based prosecution, and the drug treatment program are two new ideas to be implemented by me, as Commonwealth’s attorney. I am convinced, and I have no doubt about it, that at the end of the day, Roanoke will be a safer city after I become Commonwealth’s Attorney.

Why do you feel like you need to run?

One, it’s my opinion from being involved in criminal law for years, we do a pretty good job of incarcerating. Police are very good, they’re professionals, if a crime has been committed, they can prosecute. My point is, why can’t we get involved in more than just prosecution. What’s stopping us from being involved in all kinds of intervention programs that the city has to offer, whether it’s nonprofit organizations, city-run programs, churches and schools, wherever it is, and the objective would be to prevent people from being involved in crime. Specifically, I see Commonwealth’s Attorneys, people going to young people to explain to them the legal consequences. Everybody thinks, Well, you know what’s right and wrong, you know if you’re wrong, you get in trouble. But I’ve talked to young people. They don’t have any idea what they’re facing. And, just for example, there’s a minimum mandatory of five years for a felony with a gun, two years if it’s a non-violent felony, five years if you’re selling drugs and you have a gun, if you have multiple prior convictions you’re looking at five years or 10 years for a certain amount of meth. Trust me, the average person doesn’t understand. Trust me, the average criminal sitting at home does not say, You know, I’m not going to rob this liquor store because I may serve life in the penitentiary for robbery with a handgun. So these kinds of things I think we as prosecutors need to get out into the community and explain to people the seriousness of the consequences, and that there’s a better way of living. Hopefully, and it is a hope, granted, that people will stop and think before they get involved in stuff like that.

Did you learn anything from your previous run in 2017 that you’re going to apply to this one?

One, it looked like everybody didn’t know I was a Democrat, even to this day. I went back and looked at the precincts and I lost by [1,779] votes. So the first objective of this run is to make sure everybody knows I’m a Democrat. The second objective is to make sure I target those precincts that I lost, because I don’t necessarily have to win every precinct, but I have to increase my vote total in those that I lost and I will be targeting those.

The big point that Don Caldwell pulled out of his back pocket during the race last time was your business issues. Is he going to be able to play that card again?

I don’t think so. I have contacted Optima Tax and they’re resolving those issues as we speak.

Did you say resolving or?

Yes, resolving. And the other thing, one has nothing to do with the other. I mean, I’m a businessman. I go out and I earn money, and running the Commonwealth’s Attorney’s office is completely different than running your own business. Number one, I have to go out and earn the money, whereas if you’re a Commonwealth’s Attorney, the money is sort of given to you by the state, either by state or federal government in the form of grants or whatever.

Specifically, how do you plan to push drug treatment over incarceration? How would that work?

To give you a real concrete example — this happened in another jurisdiction, not in Roanoke City — I had a client who was actually in drug treatment. And an informant comes to him and says, Can you get me anything? And the guy says sure. And this is all on video tape, so there’s no dispute about the facts. He goes to a house, buys the drugs, keeps some of the drugs for himself and gives it to the informant. And the informant then gives it to the police. Technically, that’s a distribution. It was prosecuted as a distribution. But even the pre-sentencing report said this was a drug user, but he was sentenced to, like, three-and-a-half, four years in the penitentiary. And he was sentenced as a drug seller or dealer. And he wasn’t. Specifically, that’s the first thing I’ll do. Everyone will be identified as, Are they really a drug dealer and he’s making a ton of money? Or is he just a drug user trying to satisfy his own habit? If he’s a drug user, I don’t think he actually sold drugs, though it’s technically a distribution, he’ll be reduced to a possession and he will be given the opportunity, depending on the circumstances, whether it’s in-patient drug treatment or the Alpha program, or out-patient through Blue Ridge Behavioral Health.

What’s your position on the recent legalization of marijuana, from a prosecutor’s point of view?

People have got to understand, while it’s legal to possess small amounts, it’s still illegal, for example, to drive under the influence. I would like to see years of, you know, how is this working in actual practice. But ultimately it’s up to the legislature and whatever they decide to do is fine with me.

Caldwell’s issue is it takes away a probable cause element that prevents police from making searches. His argument was, when you find marijuana, you find guns and harder drugs. Do you give any credence to that?

I disagree as a defense attorney. I think the problem with the way the law was, it means that if an officer came up to your vehicle, he stopped you for speeding, and he said he smelled the odor of marijuana, that gave him authority to search. For the probable cause to believe that an illegal drug is in the car. I would like to see some figures on that, because I don’t think that’s necessarily true. A lot of young people smoke marijuana, and they are not drug dealers, they may not have guns. They don’t have harder drugs, and so forth. So again, unless there’s some figures out there that I have not seen, I don’t think that’s necessarily accurate to say, because of the smell of marijuana, you’ll find other illegal activity. I think police use that to search, and I have had a number of cases, more from the defense attorney’s point of view, that nothing else is found, maybe some marijuana. And that will be the end of it. No guns, no other hard drugs or anything like that.