Nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord play prominent roles in our ability to control many of our muscles, including those in our arms and legs. However, one disease has the power to take away this control seemingly at random.

According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that progressively destroys motor functioning in people usually between the ages of 40 and 60. Some cases are linked to heredity, and the remaining 90 to 95 percent seem to only affect certain people, leaving its cause largely unknown.

Virginia Tech researchers are exploring the origins of this disease by investigating its relationship to aging, and whether or not the disease can be characterized as accelerated aging.

According to the research of Gregorio Valdez, an assistant professor at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and department of biological sciences in the College of Science, the answer to this question may be found by studying synapses, the sites that neurons use to communicate with each other and with skeletal muscles.

This summer, Valdez brought on two undergraduate students – Zachary Kemp of Roanoke, Virginia, and Austin Tatum of Oak Ridge, Tennessee – as part of the Fralin Life Science Institute’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship program to study how aging and age-related neurological diseases, such as ALS, affect motor functioning.

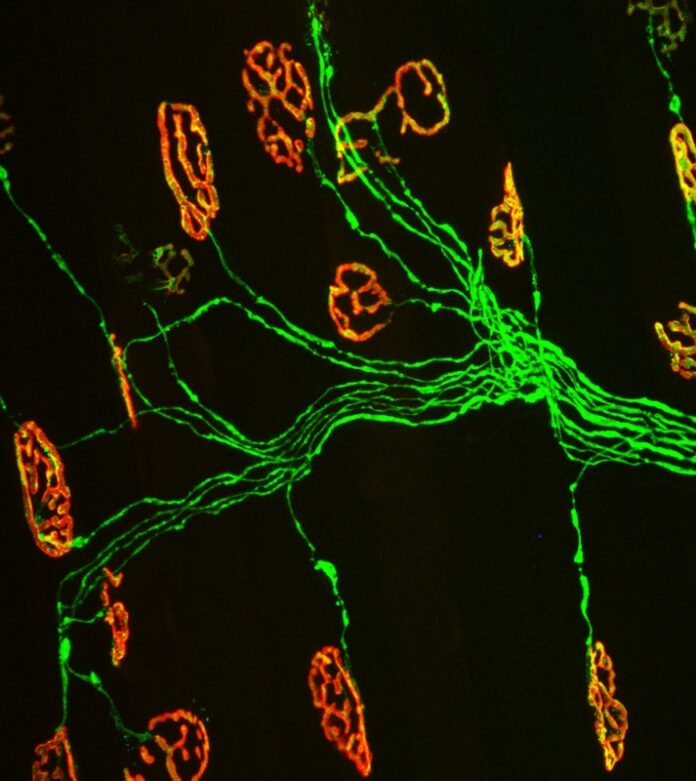

Kemp, a sophomore majoring in biochemistry in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, studies when and how ALS disrupts the motor system. Specifically, he has been studying the communication bridge between skeletal muscles and motor neurons– synapses called neuromuscular junctions.

This bridge allows the brain and spinal cord to communicate with skeletal muscles. As people grow and develop, these connections become stronger, allowing people to crawl, walk, run, chew, and swallow. With advancing age, however, the neuromuscular junction falls apart, preventing the normal exchange of small molecules that muscles and neurons need to survive, according to Valdez.

ALS has a similar effect on the neuromuscular junction. It causes degeneration of axons and death of the motor neurons, resulting in the rapid decline of motor skills, paralysis, and eventually death.

“In ALS, it may be that skeletal muscles and motor neurons fail to properly connect, or that everything develops just a tad too fast, in which case ALS becomes an accelerated form of aging in the motor system,” said Valdez. “Physical activity as well as dietary intervention can slow destruction of neuromuscular junctions that occur with advancing age. It is then conceivable that fine-tuning neuronal activity within the motor system may slow the destructive effects that ALS-causing mutations have on neuromuscular junctions.”

In an attempt to understand the connection between neuronal activity and the wellbeing of the motor system, Tatum, a senior majoring in psychology in the College of Science, investigates changes at synapses further up in the nervous system hierarchy at the spinal cord.

“My project takes a step back and looks within the spinal cord where we don’t know as much about the effect of ALS and aging on the connections that different types of neurons form on motor neurons, the cells primarily affected by ALS,” said Tatum. “I’m interested in figuring out ways to keep motor neurons alive. Modulating the level of acetylcholine release in motor neurons could allow these cells to stick around longer in individuals with ALS.”

Tatum is on a mission to explore how varying levels of acetylcholine – the neurotransmitter that drives motor activity – affects the ability of motor neurons to fend off ALS-causing mutations.

“I’m asking: What happens to synapses in the spinal cord and on motor neurons when cholinergic activity is lowered or enhanced? Are motor skills preserved and life prolonged when the cholinergic system is tampered with in animal models for ALS?” explained Tatum.

Putting Kemp and Tatum’s work in conversation with research conducted by Caleb Wood of Laurinburg, North Carolina, a junior majoring in mathematics in the College of Science, makes it possible to correlate cellular, molecular, and behavioral changes resulting from normal aging and ALS-causing mutations. Wood studies the role physical activity plays in muscle aging by investigating cholinergic activity at the neuromuscular junction and, like Tatum, correlates cholinergic activity with behavioral performance.

These three projects inform each other in that ALS and aging impair motor function. The biochemical makeup of cells and molecules in the spinal cord will inevitably affect bridges down the line at skeletal muscles and the functioning of motor skills.

“There are a lot of leads,” said Valdez. “But we need to know the specific areas of the spinal cord and musculature first affected in ALS. We are trying to pinpoint the culprit, and our research indicates that it may be the circuit, the connections in the spinal cord and on skeletal muscles.”

Improving wellbeing is part of the goal for Kemp and Tatum’s summer research, which will inform treatments for ALS and other neurological diseases.

“Having two family members pass away from ALS, I’m excited to see what my project can do for the medical community in the long run. If neural development is altered, then the disease could potentially be attacked with pharmaceutical intervention,” said Kemp. “These disease mechanisms may also reveal early patient care strategies. If anti-aging therapeutics could prove to be effective for impacted patients, it could make huge strides in providing a higher quality of living while delaying onset.”

During the summer of 2014, approximately 31 students are participating in Fralin Life Science Institute’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship program. Students receive funding to pursue full-time independent research projects under the guidance of a faculty mentor. Project results will be presented at the Virginia Tech Summer Undergraduate Research Symposium held from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Thursday at the Graduate Life Center.

– Cassandra Hockman